No End In Sight: Networked Art as a Participatory Form of Storytelling

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 To comment on SPECIFIC PARAGRAPHS, click on the speech bubble next to that paragraph.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 When you start community-building, what you need to be able to present is a plausible promise. Your program doesn’t have to work particularly well… What it must not fail to do is convince potential co-developers that it can be evolved into something really neat in the foreseeable future. – Eric Raymond, The Cathedral and The Bazaar

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The question of a cohesive factor then becomes increasingly associated with the stories that hold together, or at least define, a network as a structure distinct from other, more hierarchical forms of organization. The ability to tell stories in turn involves the capacity to disseminate those stories — that is, to be heard, read, understood, and to convince those who are the ‘targets’ of the stories, and thus the potential nodes or components of the network. – Samuel Weber, Targets of Opportunity

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Eric Raymond’s and Samuel Weber’s reflections emphasize an aspect of network culture frequently overlooked by new media theory: the relation between networks and narratives. Both theorists assume that when it lacks a single center or leader a network can grow or expand, endure or collapse, depending on the appeal of the stories it produces.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 In his seminal text on open source culture, Raymond analyzes the dynamics of cooperation, self-organization and information-sharing underpinning the development of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). Within a gift economy such as the open source economy, striving for consensus, he argues, means presenting “a plausible promise” to which a high number of programmers may respond at the moment of the launch of a new developing project.[1] Because in its early stages FOSS development is rarely retributed, programmers value other factors such as the project coordinator’s reputation, and the possibility that the software may become popular over the years. A successful collaboration inevitably bolsters a programmer’s prestige within the open source community — a prestige he/she can subsequently spend in more ambitious and possibly remunerative projects.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Focusing on the pragmatics of storytelling, Weber’s text begins with a discussion of netwar as confrontation between networks, to focus in the second part on the emergence of Jewish messianism, understood here as a diachronic network, i.e. a tradition spanning over two millennia with no clear originating point nor end. Weber draws inspiration from Networks and Netwars (2002) an influential essay published by John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, both researchers at RAND Corporation. By reviewing different typologies of networked organizations, doctrines and strategies such as the Zapatista movement in Mexico, the Colombian drug cartels, the Chechen guerrilla, and the International Campaign to Ban Land Mines, Arquilla and Ronfeldt pose a simple question:

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 What holds a network together? What makes it function effectively?[2]

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The answer is disarmingly simple: when a network lacks a single center or a leader, it is held together “by the narratives or stories that people tell.”[3]

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Obviously, from an ontological standpoint, the quest for eternal salvation of the Jewish nation has little in common with the dream of a world liberated from proprietary software shared by people of various nationalities and (religious) beliefs. Nevertheless, the two worlds are not so far apart when we consider that FOSS developers and the Jewish community are both held together by a promise — plausible and foreseeable for the former, transcendental and messianic for the latter.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 But what is a (plausible) promise if not a story aimed at setting things in motion? As Weber points out, lacking a single center or leader, a network must rely not only on the appeal of the stories it produces, but also on the “capacity to disseminate those stories-that is, to be heard, read, understood, and to convince those who are the ‘targets’ of the stories, and thus the potential nodes or components of the network.”[4]

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Whether this ability to disseminate a story is a subjective quality bearing on a narrator operating within a network, or whether it is an automated feature built into the network itself is something I will discuss in more detail towards the end of this chapter. For now, I shall just notice that in searching for a ‘cohesive factor’ Weber quietly shifts the emphasis from the subject or content of a narrative to the modality through which a story is disseminated and received by an audience. Similarly, Raymond’s emphasis on the feasibility of FOSS development implies that a good storyteller is knowledgeable of the resources a project might activate.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Shifting the focus on the pragmatics of storytelling is particularly relevant to an analysis of those narratives designed for a networked environment such as the Internet. Here even if author and audience do not share the same locale, in comparison to older media such as cinema, the printing press, and TV — which generally involve a low level of feedback between sender and receiver — they can more easily interact and enter a dynamic relationship, which may in turn affect the development of the storyline. In other words, a narrative designed to leverage the built-in feedback systems of the Internet will not be analyzed independent of its mode of circulation, that is, disjuncted from the quantity and quality of interactions it is able to activate among the nodes of a network.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Obviously, in order to be defined as such, a narrative must satisfy certain criteria. According to Mieke Bal, a narrative text presupposes the organization of a series of elements — what she calls “the material of a fabula” — according to a certain logic. These elements include the presence of actors (an actor endowed with distinctive human traits is a character), and the unfolding of events which mark a transition from one state to another. While the author is responsible for ordering the material of the fabula, the narrator, who can either be bound to one of the actors or external to the fabula, guides the reader’s attention to some aspects of the story (although for Bal the narrator should not be identified with the holder of the “point of view,” or “focalizing agent”).[5]

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 On the Internet, all these elements can be easily reshuffled so that the different functions and subject positions attributed by narratologists to authors, primary and secondary narrators, characters, and readers appear blurred. Such a confusion is primarily due to the fact that, thus far, narratology has been predicated upon the analysis of relatively stable texts such as the film and the novel. While the fruition of those texts may change over time — as they are reprinted, digitized, and adapted to new formats — their inner structure and organization remain virtually unchanged.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 A text circulating on the Internet, on the other hand, is much more malleable and can keep changing over a short period of time. Typical examples are the numerous versions of virus alerts, various forms of spam, solidarity chains, and other calls to action which spread virally online on a daily basis. Regardless of whether they are genuine or malicious, those messages usually take the form of short narrative emails that after presenting the receiver with a certain scenario ask her to perform an action, be it forwarding a message to friends, calling a phone number, running an anti-virus, connecting to a web site, signing a petition, etc. Thus, the reader is asked to become a character, and possibly a narrator in the story conveyed by the message she receives. On the other hand, readers are presented with multiple versions of the same story, which vary as they are linked, forwarded, edited, and commented upon in different contexts such as mailing lists, web sites, and social networks. As we shall see, this constant evolution of the same story is quite similar to that of oral culture wherein storytellers adapt the same story to the different audiences they are addressing.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Thus, I will begin this discussion of networked art as a participatory form of storytelling by isolating three distinctive features in those narratives which are designed for, and circulated in a networked environment:

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 1. A networked narrative describes an initially unsolved situation, a conflict, a clue, or a dilemma (denotative function);

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 2. A networked narrative demands its addressee to undertake action and play a role in it (performing function);

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 3. A networked narrative allows for the transmission of a set of rules, an ethics, or a system of beliefs that resonate with the nodes of the network to which it is addressed (pragmatic function).

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 These three levels are folded into one another or arranged in a hierarchical fashion in that each of them requires the previous one(s) in order to function. Simply put, actors cannot play a role in a story without a story, and can hardly make the ethics conveyed by the story their own (and possibly affect it) if they do not participate and experience the narrative in first person.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 In order to unpack those points, I will first compare the interactive features proper of networked narratives with those of oral culture, and then contrast them with the purported interactivity of hypertext narratives and other forms of electronic literature. Then, I will offer a few examples focusing on those networked narratives designed and executed by the net.art community over the last two decades. To conclude, I will reflect on the mutated conditions of possibility for networked art in the age of Web 2.0.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Beyond Hyperfiction

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 To begin with, it must be noted that the advent of electronic media and of dense information networks has faciliated a revival of some aspects of oral culture or a “secondary orality,” Walter J. Ong’s suggestion that, while based on the permanent use of text, presents a “striking resemblance to the old in its participatory mystique.”[6]

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 As Walter Benjamin noticed, in oral cultures the traditional storyteller was always part of the story she was telling, either because she experienced it directly or because she had heard it from someone else. A highly visible narrator, the oral storyteller interfered with her account as much she liked, occasionally partaking in the action as one of the characters. Furthermore, the storyteller encouraged her audience to continue to tell stories, so that the listener gained potential access to the same authority as the storyteller simply by listening.[7]

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Jean Francois Lyotard has observed that this kind of knowledge involved a threefold competence that went well beyond the denotative content of a story: knowing how to tell a story; knowing how to listen to it; and knowing what role to play in it. In other words, the acts of narrating, listening, and performing contained a series of norms (the how-to’s) that allowed for the reproduction of a culture. According to Lyotard, this pragmatic knowledge “defines the community’s relationship to itself and to the environment… what is transmitted through these narratives is the set of rules that constitutes the social bond.”[8])

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 In order to understand how online communication can recuperate some aspects of this pragmatic knowledge I will now contrast the concept of hypernarrative or hyperfiction to the narrative machines developed by the net.art community.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 To begin with, it is interesting to notice how the early 1990s’ promise that hypertext would revolutionize the world of literature has virtually disappeared from the cultural horizon of the new millennium. In spite of the attempts to commercialize literary CD-ROMs and software for creating and editing hypertext narratives, hyperfiction as a genre never really took off in the marketplace.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 One of the reasons for such macroscopic failure is probably to be found in the resilience of the Barthesian “pleasure of the text,” that is to say, in the reader’s choice to surrender to the power of a narrative, and to its author.[9] If Barthes saw reading as an erotic experience of language, Benjamin connected it to death. According to the German philosopher, the reader draws her pleasure from surviving the end of the novel, as it is only by attending the exhaustion of the plot and the (figurative) death of the characters that she grasps the full meaning of their existence.[10] Now, if under the print paradigm, eros and death ensure the faithfulness of the reader to the text and to its author, hypertext seemed to hold the promise, at least for a while, of shifting the power balance in favor of the reader. For instance in the early 1990s, hypertext theorist George Landow drew on Barthes’ distinction between the readerly and the writerly text to note how electronic hypertext had the power “to make the reader no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text.”[11] And yet, in the ensuing decade, online and offline hypertextual narratives never became a popular genre beyond limited circles of literary theorists and experimental writers.[12]

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 The fact is that when hypertext does not provide the reader with authoring tools and advanced feedback systems — as in the case of most circulating hyperfiction — it just ends up reinforcing the author’s position, conversely disempowering the reader. As a matter of fact, the trade-off between giving up the voyeuristic pleasure of surrendering to a story and the ‘freedom’ of choosing among a number of alternative options by following trails of hyperlinks, is clearly disadvantageous to the reader. Why should she renounce such a pleasure to enter a world whose fuzzy boundaries escape her?

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 To be sure, postmodern authors such as Borges, Queaneau, Calvino, Cortázar and contemporary filmmakers such as David Lynch, have managed to undermine the linear order of the fabula by designing nonlinear or multilinear stories with forking subplots, multiple beginnings or multiple endings. However, the physical properties of the codex and the temporal boundaries of the object-film have always endowed the reader/viewer with absolute sovereignty over these artifacts. It is those limits that made Barthes’ famous reflections on the death of the author possible. According to the French semiologist “a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination,” that is, in the reader’s ability “to hold together in a single field all the traces by which the written text is constituted.”[13 But if the experience of reading can be contained in a single field, it is because the book crystallizes in a continuum that coincides with the experience of reading "all the quotations that make up a writing."[14]

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 With hypertext such a continuum is blown open. A hyperfiction or hypernarrative, especially when it resides on the Internet, is not only open to multiple interpretations (like any other text), but entails forking, sometimes mutually exclusive readings. In other words, its polysemy rests on the semantic level no less than on a topological level, that is, on the level of the physical and logical arrangement of the elements that compose a hypertext. This means that a hyperfiction’s unity lies no longer — as in the case of books and films — in its destination but rests firmly in the hands of the author, who usually retains exclusive access to the files and folders which support the hypertext’s diagram.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Thus, the author can force the reader to follow specific reading trajectories by placing topological constraints in a hypertext. As Espen J. Aarseth has pointed out, this implies that the reader cannot freely skip and skim passages, thereby fragmenting the linear text expression, as in the process of reading a book. “Hypertext reading is in fact quite the opposite,” writes Aarseth. “As the reader explores the labyrinth, she cannot afford to tread lightly through the text but must scrutinize the links and venues in order to avoid meeting the same text fragments over and over again.”[15]

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 Now, if in spite of the truism that hypertext is an inherently interactive and democratic medium, works of hyperfiction often end up empowering the author, this is because new media bring to the foreground what Lev Manovich has described as the cultural logic of the database. According to Manovich, the database is a cultural form that privileges the paradigmatic over the syntagmatic dimension because it presents the user with lists of objects and collections of data whose connection with one another is extrinsic to it. “A database can support narrative,” Manovich notes, “but there is nothing in the medium itself that would foster its generation.”[16] To be sure, the interface to the database can channel, as we just said, the reader’s choices. But every time a hypernarrative bifurcates presenting the reader with alternative options, “she is made aware that she is following one possible trajectory among many others.”[17]

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 What we face here is thus not the death of the author, but the death of the authoritative role of teleological closure; that is to say, of the very possibility for the reader or listener of extracting meaning and pleasure from the clear ending of a story. The consequences of this indeterminacy or lack of form are dramatic: a hypernarrative involving alternative reading trajectories produces as many publics as the number of available readings. Being aware of the partiality of their experiences, hyperfiction readers have a hard time sharing them. As the author hides behind a maze of hyperlinks, her community of readers fails to reach a critical mass. This fragmentation of the readership results in the impossibility of solidifying a critical debate that has a cultural relevance within the social fabric, as in the case of cinematic and literary works.[18]

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 But the inability of hyperfiction to have a significant cultural impact is not to be identified with a failure of truly interactive and participatory narratives. The readers can in fact challenge the opacity of hypernarratives by becoming “metareaders,” by trying to trace the map of their own readings — a move that Aarseth defines as “a strategic counterattack upon the limited perspective offered to the reader by the hermetic text and an effort to regain a sense of readership.”[19]

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 When a hypertext does not embed functions that facilitate its own mapping, this “counterattack” can be pursued by making use of a variety of tools. For instance, with the help of an offline browser, users can download a web site and visualize its underlying topology on their local hard drive. Then they can modify it, republish it, link it to and from other web sites, search engines, mailing lists, or even simply transcode it with a software that can yield surprising results. In other words, by making creative use of existing software, or designing software of their own, users set out to learn those pragmatic rules that allow for the production and circulation of information within a networked environment. Now, my contention is that it is precisely at this level that we approach the domain of networked art.[20] When a reader discovers unforeseen and creative ways of reading a story, she begins to cross over to an authorial position. Conversely, the author becomes a spectator who has now little control over her creation. This role exchange however is neither symmetrical nor a zero-sum game, because the reader’s use of “unauthorized software” breaks the unilateral agreement the author has built into her narrative by choosing a specific software to design it, and a specific interface to visualize it.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 In the 1990s, net.art groups such as 0100101110101101.ORG, ®TMark, The Yes Men and net.artists such as Cornelia Sollfrank, Vuk Cosic, Rachel Baker, and Mark Napier made an art of cloning, parodying and remixing commercial, political, and even art sites. By either using available offline browsers and FTP software, or creating their own applications which randomly generated ready-made web sites, these artists show us that not only are decoding tools never neutral, but that on the Internet the user can make her own tools for hacking new information out of the old.[21]

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 The Faker As Producer

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 As previously noted, spoof sites which target a politicians or a corporation, or art browsers which advance an aesthetic interpretation of HTML (such as Mark Napier’s “Riot” or Jodi’s “Wrongbrowsers”) are hardly narrative objects. Some of those projects may contain narrative elements — e.g. the “About” page of a spoof web site may feature a narrative description of a company’s history or mission, but in general, and especially in the case of software, they should be read as statements, rather than stories, about a variety of aesthetic and political issues.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Nevertheless, if we consider these projects not in isolation but in relation to one another, a pattern begins to emerge. ®TMark is a case in point. Launched in the mid-1990s as a pseudo-corporation engaged in the peculiar business of “correcting the identity” of other corporations, ®TMark spun corporate aesthetics, language, and PRs to embarrass conservative politicians, gaming companies, and environment-unfriendly corporations. After executing hilarious stunts such as the spoof web sites of Rudolph Giuliani, George W. Bush, and the Shell corporation, switching the voice boxes of talking Barbies and GI Joes, promoting the illegal sampling, remixing and distribution of music, and inserting homoerotic scenes in a first-person shooting game, the group became a prominent culture jamming hub, listing on its web site dozens of possible subversive projects, many of which were suggested by third parties.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0

®TMark

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 Serving as an umbrella-organization and a matchmaker between different agents, ®TMark laid down its (anti-) corporate mission in the following terms:

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 The core of the ®TMark system is a database of unfulfilled sabotage projects. Each of these projects has four simple keys: the worker, the idea, capital investment, and ®TMark’s corporate veil. The first key to any ®TMark project is the idea. A project idea can be submitted through RTMark.com by any party, including the proposed worker or funder… The worker is the most important key to any ®TMark project. Widespread corporate use of internet resources assures that ®TMark’s workers represent a diverse cross-section of the population. The third ®TMark key is anonymous capital. Although most workers do not perform ®TMark actions for the sake of gain, financial rewards can provide a small measure of comfort, or inspiration. Finally ®TMark provides the “corporate veil” that displaces liability from funder and worker. ®TMark also helps maximize the project’s performance and profile with public relations efforts that highlight intrinsic key issues.[22]

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 At least three of the four keys listed above belong to what Bal calls “the material of a fabula.” While the worker and the sponsor act as characters (the worker is the hero, the sponsor one of his or her allies), the product to be sabotaged is an object of desire (Ball calls it “object of intention”), i.e. the element that sets the drama in motion.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 The idea, on the other hand, constitutes the original script from which ®TMark weaves the elements of the fabula into a story. This process is done in several stages. On one level ®TMark’s function within the fabula is to provide “a ‘corporate veil’ that displaces the liability from funder and worker.”[23] (Because in the U.S. corporations are people before the law, CEOs and managers take advantage of the corporate persona to deflect their personal liability; ®TMark appropriates and reverses this process by offering a legal shield to those who engage in corporate sabotage.) On a different level ®TMark acts as a storyteller who “helps maximize the project’s performance and profile with public relations efforts that highlight intrinsic key issues.”[24] By emailing witty press releases to a vast network of journalists and media operators, ®TMark allows them to cover stories, from an entertaining angle, that would otherwise remain untold.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0

®TMark: Bringing It To You, 1998

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Moreover, once the story of a sabotage is reported by the media, the targeted individual or organization is prompted to provide a quick response, which usually takes the form of a threat or disavowal. The counterpart’s reaction allows ®TMark to effectuate a countermove, which yields in turn a new round of news stories. In general, continued media exposure does not play in favor of characters/actors whose motivations are utilitarian (e.g. increasing profit or collecting votes) and who take themselves quite seriously. Conversely, it favors those characters whose motivations are idealistic and who use the weapon of irony.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Besides showing how the Internet fosters a dramatic leveling of the playing field in public relations, ®TMark’s ability to move between different narrative and performative levels presents striking similarities to the participatory aspects of oral culture. First, the group sets up a narrative framework by which an activist intervention can be presented as drama (and through which the public is driven to identify with the “good guys.”) Second, rather than acting as an external or presumably ‘neutral’ narrator, ®TMark takes part in the narrative as a character. Third, the group encourages the public to continue to tell stories by providing on the one hand a public database of subversive projects (which can be executed by anyone); and on the other hand a series of tools and recommendations for hacking and social engineering.

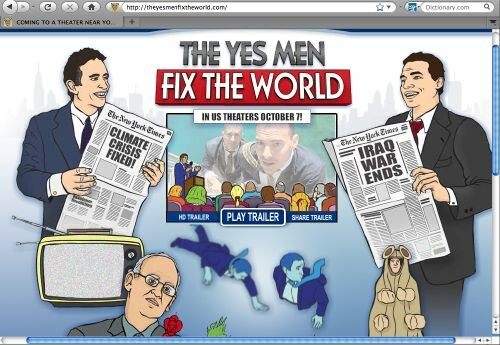

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 For instance, in 1999 the group released Reamweaver, a software that, installed on a server, enables users to emulate the style and content of any static web site, and to update it in real time. First tested on gatt.org to spoof wto.org — the official web site of the World Trade Organization — the software has been subsequently used by The Yes Men, an offshoot of ®TMark, to run a number of corporate web parodies. The main difference between The Yes Men and ®TMark is that the former have emphasized the theatrical and narrative aspects of the anti-corporation’s PR strategy by developing two actual characters (Andy Bilchbaum and Mike Bonanno) who confront corporate CEOs and politicians in real-life.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 By promptly responding to incoming emails and invitations from journalists and conference organizers who frequently mistake the spoof web sites for the official ones, The Yes Men have been able to represent the WTO, Dow, Exxon, and Halliburton in various international conferences and even on TV. With the aid of PowerPoint slides, 3D animations and theatrical props, the group has given a series of surreal lectures that take to the extreme known neo-liberal arguments, cheerfully proposing sinister solutions to global problems such as third-word starvation, oil shortages, and global warming.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 Over the last five years, The Yes Men’s lectures have been documented and edited into two feature films, The Yes Men (2004) and The Yes Men Fix the World (2009), which are both manifestoes of the “Trojan-horse activism” of the twenty-first century and a bleak portrait of the complacent elites of our time. Not incidentally, The Yes Men have chosen to organize the elements of the fabula (the lectures) in a quintessentially narrative format such as the docufiction. While ®TMark gave a syntagmatic expression to its database of subversive projects in the form of multiple press releases — but also had to measure the success of their stunts in terms of media exposure (thus delegating part of their story-telling to journalists) — The Yes Men have assumed full narrative control over their interventions by using the Internet to produce them, and cinema to turn them into (layered) stories.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0

The Yes Men Fix The World, October 2009

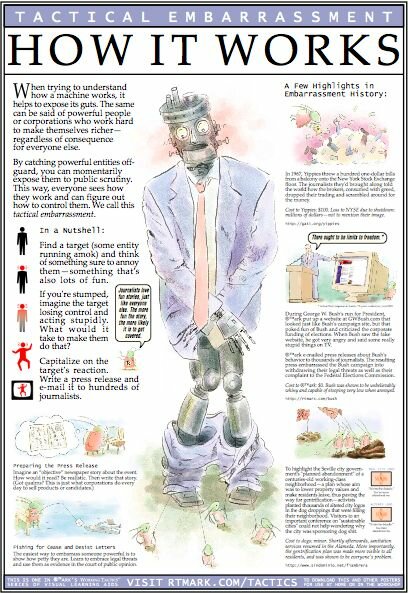

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 Returning to a traditional medium such as film for story-telling has also another consequence, namely, the multiplication of audiences. In fact, a spectator of a Yes Men film is invited to assess the reaction of the corporate audiences attending their lectures, who become unknowing characters in the story. Although the overall effect is apparently comic, in that the conference attendees generally approve rather than reject the ruthless if imaginative theses advanced by Bilchbaum and Bonanno, there is also a tragic element to it. As Jeanne-Pierre Vernant has demonstrated in his study of Greek tragedy, the irony of tragedy resides in the human misunderstanding of the meaning of words, whose ambiguity leads to various conflicts between the hero and other characters. To the spectator however, the duplicity of words is perfectly clear:

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 It is only for the spectator that the language of the text can be transparent at every level in all its polyvalence and with all its ambiguities. Between the author and the spectator the language thus recuperates the full function of communication that it has lost on the stage between the protagonists in the drama. [25]

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 Since, in our case, the authors of the film coincide with the heroes of the story, and their interventions do not lead to tragic endings, the drama resides in the fact that the difficult questions posed by the authors (how to solve the problems that afflict the world) go unanswered, rather than in an irreconcilable conflict between the characters.

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 The spectator is thus invited to assume the ethical stance of searching for solutions, and to keep posing uncomfortable questions to those who have the power to provide answers. In order to prompt the audience to assume such a position, that is, to transform the spectators into a network of collaborators, The Yes Men keep using the Internet to articulate the pragmatic rules of their narrative strategy. Thus, not unlike ®TMark, The Yes Men release DIYs for “tactical embarrassment” and “identity correction” that reveal the behind-the-scenes of their stunts.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0

®TMark: Tactical Embarrassment, 2001

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 A recent example is Fix The World Challenge an exhilarating compilation of tips for aspiring Yes Men that explains how to “Create a Ridiculous Spectacle,” “Crash a Fancy Event,” “Correct an Identity Online,” “Hijack a Conference” and so forth. By simply logging into a WordPress blog users can join online groups, upload videos, and coordinate for direct actions with the promise that the best interventions will be featured in the DVD of the next Yes Men movie, and shown before screenings. [26]

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Furthermore, the network is also able to produce valuable tools of its own, which are in turn useful to The Yes Men. For instance, the Italian art group Les Liens Invisibles has developed A Fake is A Fake, an evolution of “Reamweaver” that enables users to forge and parody authoritative themes such as those of nytimes.com, lefigaro.fr, ft.com, repubblica.it, whitehouse.gov and to run them on any WordPress site. This software has been employed recently to run the online version of a fake Special Edition of the New York Times, a collaboration between The Yes Men and several activists which announced the end of the war in Iraq right after the election of Barack Obama to President of the United States, and then again, in September 2009, to run a fake Special Edition of the New York Post, focusing on global warming and climate change.

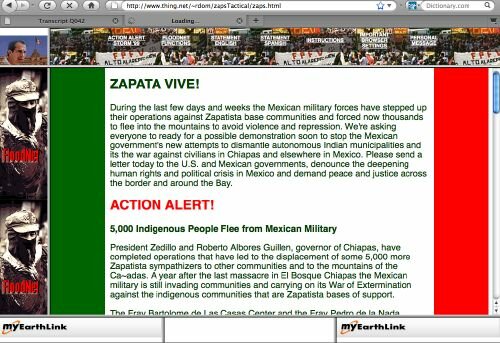

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0

The Yes Men, Fake New York Times Special Edition, November 2009

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 Thus, we see how the networked narrative set in motion by The Yes Men links and mobilizes multiple publics. While the spectators of a Yes Men’s movie are invited to reflect on the tragic nature of our present condition (here is the cognitive, denotative function of storytelling) the very same spectators are also encouraged, along with Internet users, to become players and characters (performative function) in a game whose initial rules are loosely set by the group, but whose actual development is determined by the users themselves. Furthermore, when a node of the network designs a piece of software such as A Fake is A Fake, it sets the conditions for generating new modes of interaction and possibly new rules of the game (pragmatic function). As we shall see in the following sections, it is precisely through the combination of the denotative, performative, and pragmatic function of storytelling that users can cross over to an authorial position.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 Hacktivist Narratives

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 The creation and evolution of toolkits which stem from sociopolitical practices such as pranks, fakes, and culture jamming is not unique to The Yes Men network. As a matter of fact, it is a common practice within the so-called ‘hacktivist community,’ which merges the skills of computer hacking with activism.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 In 1998, the Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT), a radical art group co-founded by Ricardo Dominguez, Brett Stalbaum, Carmin Karasic, and Stefan Wray, released the Zapatista FloodNet, a Java applet that facilitates virtual sit-ins by automatically reloading the web pages of any target URL. Originally created to obstruct the web site of the Mexican government as a form of protest against the repression of the indigenous movement in Chiapas, and subsequently released as an open source software that could be further developed by third parties, the FloodNet became popular in the heydays of the anti-globalization movement, when hundreds of thousands of hacktivists launched it through their browsers to block or slow down access to the WTO, IMF, World Bank, and World Economic Forum web sites.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 In the following years, hacktivist collectives such as the Electrohippies Collective, the Federation of Random Action, and ToyZTech, added new features to the original applet that both sped up the automatic reloading (the more people launch the FloodNet the faster and higher the number of requests to the target web site) and multiplied the communication channels among participants to the virtual sit-in.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 Moreover, the tactical use of the software has been adjusted over time to the changing circumstances “on the ground.” In particular after the Pentagon built a Hostile Applet to rebuff a netstrike on its web server in 1998 (an action coordinated by the EDT during the Ars Electronica Festival), and the upstream provider Verio shut down The Thing server during the Toywar in 1999, the hacktivists decided to distribute the FloodNet as a downloadable toolkit. While with the first netstrikes the participants had to connect to the EDT server in order to launch the FloodNet, with the downloadable toolkit they could launch it directly from their client, thereby reducing significantly the risks of a counter-attack.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 The coordination of a distributed action, however, posed other problems such as the difficult verification of the number of participants, and the potential dispersion of a critical mass of demonstrators. In order to overcome these problems the hacktivists frequently set the virtual sit-in at the same time as actual street protests, and developed new tools that enhanced the interactivity of the online protest.[27] For instance, during the September 26, 2000 street protests against the World Bank in Prague, the Federation of Random Action and ToyZTech released a chat-room software that enabled users to ping the IMF’s and World Bank’s web servers every time the activists used key words such as “poverty,” “finance,” “investment,” and “financial power.” Furthermore, the software solicited error messages from the targeted servers by uploading unanswerable requests such as “Do you sell sheep shavers?” or “Our life is not for sale” — a feature that, as we shall see, had already been implemented in the FloodNet interface. [28]

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0 In this and other circumstances, the hacktivists use a rhetorical strategy that emphasizes the social and conceptual dimension of the action. Being aware of the impossibility of sharing a physical space such as a street or square, the hacktivists stress the importance of sharing a time-frame, or the subversive potential embedded in the simple choice of connecting simultaneously to a web site from all over the world. [29] In the case of the EDT this rhetorical strategy frequently takes on a performative, narrative form. Dominguez in particular has introduced a number of offline presentations of the software by wearing a ski mask and performing a story originally told by the Subcomandante Marcos. Adopting the narrating voice of Marcos, he sets the story in an indigenous village of Chiapas, which is electing its delegates to a larger EZLN meeting, while Pedrito, a two-and-half Tojolabal, is playing with a piece of wood:

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 The village is assembled when a Commander-type plane, blue and yellow, from the Army Rainbow Task Force and a pinto helicopter from the Mexican Air Force, begin a series of low fly overs. The assembly does not stop; instead those who are speaking merely raise their voices. Pedrito is fed up with having the artillery aircraft above him, and he goes, fiercely, in search of a stick inside his hut. Pedrito comes out of his house with a piece of wood, and he angrily declares, “I’m going to hit the airplane because it’s bothering me a lot.” I smile to myself at the child’s ingenuousness. The plane makes a pass over Pedrito’s hut, and he raises the stick and waves it furiously at the war plane. The plane then changes its course and leaves in the direction of its base. Pedrito says “There now” and starts playing once more with his piece of cork, pardon, with his little car. The Sea and I look at each other in silence. We slowly move towards the stick which Pedrito left behind, and we pick it up carefully. We analyze it in great detail. “It’s a stick,” I say. “It is,” the Sea says. Without saying anything else, we take it with us. We run into Tacho as we’re leaving. “And that?” he asks, pointing to Pedrito’s stick which we had taken. “Mayan technology,” the Sea responds. Trying to remember what Pedrito did I swing at the air with the stick. Suddenly the helicopter turned into a useless tin vulture, and the sky became golden and the clouds floated by like marzipan. [30]

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 The story is a parable which is meant to illustrate the power a piece of “Mayan technology” called FloodNet has to create a different type of reality. As Dominguez points out, the technical efficiency of the FloodNet is not so relevant when compared with its ability to set in motion a new “performative matrix,” an abstract, invisible theater in which contending actors (the Mexican government, the hacktivists, the indigenous people of Chiapas, the cyber-police, and so forth) come to form a social and civil drama.[31] Thus, rather than being catalogued as a physical attack on a server, argues Dominguez, the virtual sit-in should be understood as the simulation of a physical attack that operates on a syntactical and semantic level. The latter refers to using “words as war” rather than “words for war” (a lesson Dominguez derives from the Zapatistas) to create and amplify the aforementioned drama through multiple media channels. The former affects the level of code, that is, the possibility of “reversing the logic of the system, in order to make it function in a manner it was never made to do.”[32] As a matter of fact, he continues:

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 EDT’s Zapatista FloodNet used the logic of the network to upload 404 files (or Files Not Found) in order to upload political questions into the Mexican government servers during our 1998 electronic actions. Questions, like, is “justice.html” found on this server? The Mexican government server would respond: “justice is not found on this server.” Here the logic of the system was used to create a counter critique within the structure of the government’s servers, which also pointed to the real political conditions of Chiapas, Mexico.[33]

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0

Electronic Disturbance Theater, Zapatista Floodnet, 1998

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 Now, I believe that the meaning of the term “syntactical” should be expanded in this context to include not only the conflation of machinic language (the 404) and natural language (the lack of justice), but also as the re-articulation of different aesthetic, political and technological codes within a multi-layered networked narrative.

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0 In fact, the 404 is not only a glitch in a chain of web signifiers, but also a known net.art gesture. In the 1990s, the artist duo Jodi developed a distinctive aesthetics out of machinic errors — 404.jodi.org is a renomated net.art project — that was subsequently imitated and expanded by a number of artists. Since the FloodNet window is divided in multiple frames each of which can be pointed to a different URL, the aesthetics of the 404 is reframed here in a political context. In other words, the FloodNet functions as a syntagma that links the discursivity of different communities — the ability of forging tools proper to hacking, the organizing competences of activism, and the formal explorations of net.art — within a narrative and performative framework.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 As we have seen, ®TMark had given a syntagmatic and narrative expression to its database of subversive projects by organizing them in the form of press releases, which had the twofold purpose of drawing media attention and eliciting a reaction from corporate counterparts. The four narrative keys that formed ®TMark’s fabulas, however, remained on the same plane of consistency, i.e. they could be recombined only to form multiple variations of the same story, namely, the subversion of an irresponsible corporation. In the case of hacktivism, the denotative function of networked narratives is equally simple, i.e. to expose human rights abuses as well as the scarce accountability of supranational regulatory institution such as the WTO and financial agencies such as the IMF. Their pragmatic function, however, is more nuanced and open to further elaboration. In fact, the rapid development of software tools by a small but tight-knit community of hacktivists bears witness to the their ability not only to tell multiple versions of the same story, but also to retell it each time in a slightly different way by developing new tools that allow the actors/participants to perform it differently over time.

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 In other words, while ®TMark’s networked narratives are driven by the denotative function, that is, by the storyteller’s ability to make them enticing, hacktivist narratives are driven by the pragmatic function, as they revolve more heavily on software, that is, on a tool that determines the way information (and people) are concatenated. Thus if we go back to Lyotard’s reflection on the pragmatic nature of oral narratives we can see how the hacktivists who created and upgraded the FloodNet over time first learned how to listen to a story (as related by the EDT, for instance); then they learned what role to play in it (by partaking in virtual sit-ins); and eventually they learned how to tell their own stories (by sending out their own calls to action, and developing their own piece of software).

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0 Obviously, the difference between oral narratives and networked narratives lies in the fact that the latter take place in a machinic environment such as the Internet, wherein natural language is not uttered into the air, as it were, but it is transmitted as the speed of light, mediated by computer screens and graphical user interfaces, and processed through layers and layers of code. This means that “the set of rules that constitute the social bond,” to stick to Lyotard’s definition, have to be adapted here to an environment in which the community is physically dislocated, and shares only information and fragments of time. Nevertheless oral narratives and network narratives retain some common features, in that they both convey an ethics and a set of values that resonate with the community of addressees.

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 This is clearly not the appropriate context to delve into the complex systems of beliefs articulated by oral narratives. But in the case of hacktivism we can see how the network marries the hands-on approach, and the principles of sharing and open access to information that are so dear to the hacker community, with basic activist principles such as consensus-building, public exposure, and exerting pressure on the counterpart. Thus, the pragmatic function of hacktivist narratives shall not be reduced to the ability of developing a piece of software. Rather, those narratives are effective insofar as they reflect (and affect) a variety of cultural elements, enabling the members of the community to understand what matters in their own culture and play a role in it.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 In this respect, Pedrito’s story is exemplary insofar as it encompasses different facets of hacktivism, such as the importance of technological innovation (the stick), the democratic nature of hacking (Pedrito is a kid), the connection between the hacker and the community (the Zapatistas), and the emphasis placed upon imagination and linguistic creativity rather than technological efficiency for its own sake (it is doubtful whether Pedrito’s stick can really affect the helicopter, but his gesture can inspire others).

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0 The Toywar

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 Certainly, not all networked art results from collaborations among different communities, nor is all of it expressed in a narrative form. As previously noted, networking as a social practice is affected by technological development as much as by a variety of economic, cultural, and political factors that are historic in character. In the 1990s, artists, activists, hackers, and entrepreneurs shared a dream: the great disintermediation of the Internet would wipe out encrusted powers and pave the way for a new way of living and working nurtured only by ones ideas, passions and skills.

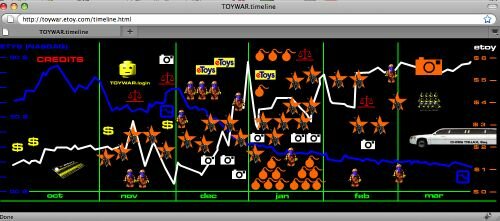

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 Even if they were driven by different ethos and motivations, those subjects were ready to share information and cooperate by the very fact of being online. The spirit of networking of the 1990s was undoubtedly present in the artistic practices of the time, so that net.art (with a “dot” in the middle) “was both an Internet-based art and an art of networking.” As I have shown elsewhere, besides being imbued with techno-utopianism, net.art that extends from the advent of the World Wide Web (1993) to the collapse of the NASDAQ (2001) was marked by three elements: the aesthetic exploration of machinic assemblages; the manipulation of information flows; and identity play.[34]

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0 If “on the Internet nobody knows you are a dog,” as a saying of the time went, then the Internet was not only an ideal ground on which to experiment with identity but also on which the concerted action of different subjectivities could possibly affect society at large. “I want to see if cyberspace is a base camp for some kinds of cyborgs, from which they might stage a coup on the rest of ‘reality’,” wrote Sandy Stone in 1995, referring to Donna Haraway’s myth of the cyborg as a powerful techno-political construct that could disarticulate Western dualisms such as nature/culture, mind/body, self/other, male/female, and the relative myths of origins.[35] And John Perry Barlow echoed her call in his famous Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace. “We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth,” wrote the co-founder of the EFF, reiterating the then popular belief in the Internet’s ability to reverse socioeconomic, gender, and racial imbalances.[36]

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 Such techno-utopianism was, among other factors, generated by the simultaneous access to online writing by a variety of subjects whose composition went well beyond the Foucauldian definition of “what is an author” under the printing press paradigm.[37] As a matter of fact, beside writers and journalists, the notion of online authorship necessarily encompasses programmers, web designers, software engineers, compulsive socializers, and in general anybody who has the ability to shape and contribute to online communication. In this context, net.art functioned as an articulatory nexus between various professional skills, discursive spaces, and aesthetic and political sensibilities.

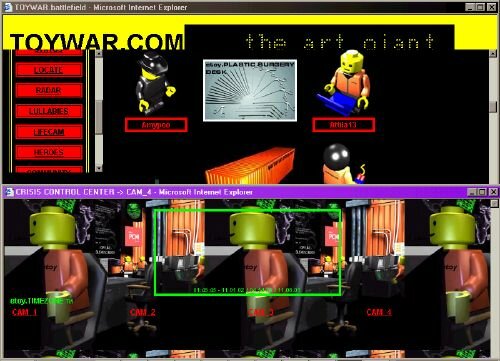

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 If the pragmatic knowledge of the oral storyteller handed down a set of rules that allowed for the reproduction of the social bond in a society whose specialization of labor was quite limited, in the hyper-specialized world of online communication those pragmatic rules are much more segmented and stratified. Knowing how to program requires a different set of skills than knowing how to grow an online community, and from knowing how to design an interface to a database or a social network. But the collaboration of those kinds of skills can recompose, at least in part, the unity of pragmatic knowledge shattered by the advanced specialization of labor in late capitalist societies.

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0 My point is that when networking does not occur within a professional or institutional framework that provides individuals with clear rewards, then it is possible only through a narrative that has the power to resonate with different communities and sensibilities. Not incidentally, some of the more enticing net.art projects rely on an open narrative or script that encourages Internet users to perform it and expand it in a variety of ways.

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0 The Toywar is a case in point. In 1999, the entire net.art network supported the art group etoy in their battle for maintaining the domain etoy.com against the repeated attempts of the online toy retailer eToys, one of the more promising dotcoms of the time, to appropriate it for commercial purposes. The battle simultaneously took the form of an online game consisting of several coordinated and distributed interventions; a campaign for artistic freedom and against the commodification of the Internet; a successful promotional operation for etoy and the net.art community; and a financial disaster for eToys, which besides renouncing to the domain name, saw the value of its shares plummet during the Toywar, and eventually filed for bankruptcy at the height of the dotcom crash.[38] In other words, the polisemy of the Toywar was generated by the interaction (and attrition) of different narrative machines such as the net art/activist communities, the media, and the stock market that distributed the same story, but attached irreducible and often conflicting meanings to it.

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0

Toywar.etoy.com, Timeline, 2000

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 By enrolling thousands of “toy.soldiers” through an originally designed web platform (now archived at toywar.etoy.com ); creating an ad hoc software called “Virtual Shopper” for clogging the eToys server with bogus shopping requests; flooding the eToys web site with a prolonged virtual sit-in at the peak of the Christmas shopping season; disturbing the company’s online trading forums by inviting eToys shareholders to sell; and compromising the company’s image in the media, groups such as etoy, ®TMark, EDT, The Thing, Hell, and several others recombined activism, hacking, and art in a new performative matrix.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0 In other words, when these communities agreed on a unifying objective — the plausible promise of regaining control of etoy.com — they gave birth to a machinic narrative whose “engine” was a dramatic script (winning the Toywar by bringing the value of eToys’ shares down to zero) that each participant could perform or execute according to her own skills, be they organizing, programming, writing press releases, web designing, or participating in online forums.

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 As a first step, etoy supporters were asked to register on the Toywar platform, where they were assigned a Playmobil-looking avatar equipped with virtual weapons. Once signed on, they could perform a series of actions such as recruiting other toy.soldiers, talking to journalists or write their own reports (media.toys), provide legal advice (lawyer.toys), upload soundtracks (dj.toys), gather intelligence on the enemy’s moves (spy.toys), disseminate info.bombs, and so forth. Finally, all the 1798 toy.soldiers who participated in the Toywar were assigned “stocks” of the etoy.corporation, and after the victorious proclamation of the end of the war, purportedly invited to have a say in the company’s future. [39]

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0

Toywar.com, Crisis Control Center, November 1999

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0 Even though etoy did not effectively turn into an art group run by such a vast community of users, the group showed that the Toywar script was multi-layered and complex enough to be executed by different nodes of the network on the basis of its peculiar skills. If “to execute in the world of code means to turn the potential power of instructions into the actual power of behavior,”[40] as Jon Ippolito and Joline Blais point out, then in the Toywar a variety of linguistic, cultural, and machinic codes were executed by different subjectivities who “worked on the base of self-organized, multi-level intelligence possible only on the net.”[41]

¶ 94 Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0 As we have seen, while ®TMark’s storytelling was mostly denotative (i.e. the stories were enticing and entertaining in and of themselves), the hacktivist community emphasized the pragmatics of storytelling, i.e. the ability to convey an ethics while envisioning new modes of interaction among the nodes of the network. Both ®TMark and EDT, however, asked participants to perform actions, such as partaking in virtual sit-ins or correcting a corporate identity, that stayed within the boundaries of an adjustable, but ultimately rigid script. In other words, the denotative and pragmatic aspects of storytelling prevailed over the performative aspects, in that those narratives offered a limited spectrum of roles that could be taken on by collaborators and contributors.

¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0 In the case of the Toywar the higher complexity of the script and the richness of the metaphors employed encouraged the nodes of the network to undertake a wider range of initiatives. Such a complexity was due to the fact that the script was designed by a broad coalition of groups (including ®TMark and the EDT) which provided a variety of insights and expertise. This high level of collaboration in the conception and design of the script guaranteed an almost perfect balance and continuous feedback among the denotative, performative, and pragmatic levels of the networked narrative, so that each intervention made the story more enticing, attracting in turn more public attention and participation.

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 0 The Withering of Net.Art and the Emergence of the Web 2.0

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0 Paradoxically, if the Toywar demonstrated that net.art had “attained the power of global agency,” (Reinhold Grether) the NASDAQ crash completely changed the scenario and the conditions of networking.[42] As Giuseppe Marano and I have argued, the burst of the New Economy financial bubble of 2000 resulted not only in a temporary reduction of the resources that supported the emerging online culture, but also marked a crisis of techno-utopian faith in the transformative capacities of new media. Once the Internet is no longer an object of libidinal investment and becomes a medium among many, desires flow back towards the rich contradictions of sensuous reality. With the molecular diffusion of wireless and GPS technologies, laptops, PDAs and cell phones, the network stretches to integrate bodies, times, and places that were originally cut off from the online world.

¶ 98 Leave a comment on paragraph 98 0 The emergence of Web 2.0 and the explosion of locative media centrifuges the libidinal surplus that had been accumulated in the “rising” and utopian phase of networking — when the Internet was both object and vector of societal desires — and disperses it towards local realities and analog practices, which can now be concatenated onto a new plane of immanence. Thus the self-referential character of early networking practices withers, relegating the aesthetics of the machinic, identity play, and the manipulation of information flows to separate spheres.

¶ 99 Leave a comment on paragraph 99 0 In the art field, the dramatic shrinking of available resources draws a line between a few successful net.artists, whose careers are increasingly professionalized, and those who now have to rely on other sources of income to make a living. In this scenario, the art world played a significant role in dividing the good, reliable artists from those whose participation in the network had been playful, gratuitous, and ultimately provisional. In other words, the general consolidation and professionalization of the new media sector inevitably confines net art to one of the many niches of new media art. In this way, net.art ceases to be an art of networking and loses, almost unnoticed, its “dot,” becoming an internet-based art (net art) without being any longer an art of networking. [43]

¶ 100 Leave a comment on paragraph 100 0 To be sure, the weakening of the networking spirit that marked the “golden age” of net.art does not mean that networked art, as a participatory form of storytelling, withers away. On the contrary, the emergence of social media and Web 2.0 fosters, as Clay Shirky has shown, the ability to form self-organized groups and undertake collective action.[44] Such a power, however, comes at a cost: the social intelligence of the Internet, and the new forms of sociality at a distance are exploited for profit-making by the corporations that make social media available in the public domain.

¶ 101 Leave a comment on paragraph 101 0 Let us finally consider the case of Google Will Eat Itself (2005) and Amazon Noir (2007) — two collaborations between the Austrian duo Ubermorgen, Paolo Cirio, and Alessandro Ludovico — that rely on basic narrative scripts.

¶ 102 Leave a comment on paragraph 102 0 Google Will Eat Itself (GWEI) can be described as an operation of self-cannibalism of the best known search engine. Bloggers and web administrators are invited to reinvest the revenues generated by the Google AdSense program from the Internet traffic on their web sites in shares of a public company, Google to The People LtD. Such revenues are increased through semi-intelligent bots that multiply the value of each click on Ubermorgen’s web site by triggering the AdSense ads placed on a network of invisible web sites. The long-term goal is to accumulate enough capital to assume control of the corporation over a certain period of time (ironically quantified in thousands of years) and eventually release its algorithms in the public domain.

¶ 103 Leave a comment on paragraph 103 0 In the case of Amazon Noir the same group of authors announced the development of a piece of software that could reproduce the digital image of any book available in the Amazon database through the software Search Inside the Book. While Amazon allows users to visualize only a preview of the text, the bots developed by Paolo Cirio executed thousands of requests per book, reassembling the complete image in PDF format. Anticipating the legal response of the company, the crew presented the entire operation as a crime story, concluded with an out-of-court settlement in which the bad guys (Ubermorgen and accomplices) caved in and eventually decided to sell the technology to the good guys (Amazon) for an undisclosed sum.[45]

¶ 104 Leave a comment on paragraph 104 0 Built upon basic dramatic plots, projects such as GWEI and Amazon Noir do not really leverage social software nor aim at activating a network of collaborators. At the same time, the network exists here as the main subject of the narrative, the battleground wherein contending forces (the users and the corporations of Web 2.0) struggle for the appropriation of value or to retain it in the public domain.

¶ 105 Leave a comment on paragraph 105 0 In the age of content generated by networked publics, corporations extract a profit from ordinary social activities such as chatting, linking, commenting, searching, tagging, posting, and so forth. On the one hand, the increasing automation and integration of these activities through social media and social software democratizes access to story-telling. As Shirky points out, the lowering costs of information sharing facilitates the spontaneous formation of groups, collaborative production, and collective action. Thus, once you have a plausible promise and the appropriate tools to fulfill it, a group can more easily agree on a set of rules whereby individual users can define mutual expectations (Shirky calls it the “bargain”), and begin working together.[46]

¶ 106 Leave a comment on paragraph 106 0 On the other hand, the fact that those activities are largely made possible by commercial services such as Google, Digg, Flickr, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and others redefines the notion of the public sphere. As is known, Habermas defined the public sphere as an institutionalized arena distinct both from the state and the market, or in Nancy Fraser’s words “a theater for debating and deliberating rather than for buying and selling.”[47] The fact that in the age of Web 2.0 those two spaces are increasingly indistinguishable — in that discussing and deliberating online are immediately economic activities — is a question that should not be underestimated by the emerging forms of networked art.

¶ 107 Leave a comment on paragraph 107 0 If the 1990s enchantment with the Internet had had the effect of bringing together artists, hackers, and activists (as well as former visionaries of the counterculture and venture capitalists), the challenge for the networked art of the new millennium is how to ensure that the new forms of collaboration take into account the materiality of their practices. While the storyteller of Web 2.0 can activate a network of potential collaborators with relative ease, the software “architecture of participation” (as Tim O’ Reilly has called the systems designed for user contribution) that allows her to do so is largely in corporate hands.[48] Thus the lowering threshold to online participatory culture has a drawback, namely a standardization of the modes of interaction, without which online social activities would be hardly profitable.

¶ 108 Leave a comment on paragraph 108 0 On the other hand though, as we just said, the sharing environments created by the Web 2.0 make story-telling available to a plurality of subjects who do not have to concern themselves with the level of code. This does not mean, however, that the pragmatic aspect of networked storytelling loses importance. Even if in a networked environment code has undoubtedly a pragmatic function in that it determines the architecture of social relationships, the move towards an increasing usability of social tools such as weblogs and social networks, D-I-Y web-based and cell phone applications, renders natural language increasingly performative and pragmatic.

¶ 109 Leave a comment on paragraph 109 0 In other words, when participation becomes generalized and imperative, only those narratives which truly matter to a community of users come to the foreground and tend to stay. Thus, now more than ever, designing stories that are simultaneously enticing, participatory, and ethical is momentous and necessary. In this respect, the wealth of knowledge and the affective spaces which emerged in the heydays of net.art from the recombination of aesthetical, political, and technological sensibilities is something should not be dissipated, but rather recoded and distributed on new planes of immanence.

¶ 110 Leave a comment on paragraph 110 0 ENDNOTES

¶ 111 Leave a comment on paragraph 111 0 [1] Eric Raymond, “The Cathedral and The Bazaar,” First Monday, February 16, 1998. Available at http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue3_3/raymond. Retrieved on August 4, 2009.

¶ 112 Leave a comment on paragraph 112 0 [2] John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt (eds.), Networks and Netwars: The Future of Terror, Crime, and Militancy, Santa Monica (CA): RAND, 2001, p. 328.

¶ 113 Leave a comment on paragraph 113 0 [3] Ibid.

¶ 114 Leave a comment on paragraph 114 0 [4] Samuel Weber, Targets of Opportunity: On the Militarization of Thinking, New York: Fordham University Press, 2005, pp. 102-103.

¶ 115 Leave a comment on paragraph 115 0 [5] Mieke Bal, Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative, Toronto: Universisty of Toronto Press, 1997, pp. 7-8 and 19-20.

¶ 116 Leave a comment on paragraph 116 0 [6] Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World, London: Routledge, 1982, p. 136.

¶ 117 Leave a comment on paragraph 117 0 [7] Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller: Reflections on the Work of Nikolai Leskov, in Illuminations, (trans. Harcourt B. Jovanovich), 1968, pp. 83-109.

¶ 118 Leave a comment on paragraph 118 0 [8] Jean Francois Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, (trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984, p. 21. It must be noted that for Lyotard (as well as other philosophers such as Bruno Latour) it is the emergence of modern science, with its claims to neutrality and objectivity, to set apart denotative knowledge “from the language games that combine to form the social bond.” (25) Here Lyotard relies on Wittgenstein’s classification of different modes of discourse in terms of rules specifying their properties, to argue that the language game of modern science pretends to answer only to the criterion of truth. This sets it apart from the realm of politics, whose language game answers to the criterion of justice, and whose legitimacy rests with the people’s consensus. This separation between the objectively observable laws of nature (denotative knowledge) and the subjective mode of deliberation through which society agrees on what is just and what is not (pragmatic knowledge), is not only a cornerstone of modernity, but also what deprives narratives of the exemplary and normative character they had in oral culture. In other words, in modern times narratives are relegated to the realm of fiction, i.e. to a kind of knowledge that by definition cannot be used to observe reality in an accurate manner because it relies on subjective human qualities such as imagination and emotions, which interfere with a rational mode of analysis. According to Lyotard, the emergence of “postmodern science” changes this epistemic model. With its search for instabilities, alternative methods, and ways of reasoning, postmodern science is for Lyotard an “open system” in which imagination plays a key role and “a statement becomes relevant if it ‘generates ideas,’ that is, if it generates other statements and other game rules.” (64) In other words, “the striking feature of postmodern scientific knowledge is that the discourse on the rules that validate it is (explicitly) immanent to it.” (54) In the reminder of this chapter I will try to show how this poietic element is also present in some networked narratives that generate new ideas and statements in the course of their making.

¶ 119 Leave a comment on paragraph 119 0 [9] Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text, (trans. Richard Miller), New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

¶ 120 Leave a comment on paragraph 120 0 [10] “Actually there is no story for which the question as to how it is continued would not be legitimate,” writes Benjamin, referring to the oral tradition. “The novelist, on the other hand, cannot hope to take the smallest step beyond that limit at which he invites the reader to a divinatory realization of the meaning of life by writing ‘Finis.’…The novel is significant, therefore, not because it presents someone else’s fate to us, perhaps didactically, but because this stranger’s fate [the character's fate] by virtue of the flame which consumes it yields us the warmth which we never draw from our own fate. What draws the reader to the novel is the hope of warming his shivering life with a death he reads about.’ Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov” in Illuminations, (trans. by Harry Zorn), New York: Shocken Books, 1968, pp. 100-01.

¶ 121 Leave a comment on paragraph 121 0 [11] Roland Barthes, S/Z: An Essay, (trans. Richard Miller), New York: Hill and Wang, 1974, p. 4. George P. Landow cites Barthes in Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology, Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1997.

¶ 122 Leave a comment on paragraph 122 0 [12] Some may argue that these promises have been fulfilled by games, with their vast interactions and sense of openness. But a gamer can hardly write the rules of the game and become the game designer (God). She can win the game or curse God, but she can rarely modify the algorithm that sets the rules of the game.

¶ 123 Leave a comment on paragraph 123 0 [13] Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author” in Roland Barthes, (ed. and trans. Stephen Heath), Image-Music-Text, New York: Hill & Wang, 1977, p. 148.

¶ 124 Leave a comment on paragraph 124 0 [14] Ibid.

¶ 125 Leave a comment on paragraph 125 0 [15] Espen J. Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature, Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University, 1997, p. 78.

¶ 126 Leave a comment on paragraph 126 0 [16] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001, p. 228.

¶ 127 Leave a comment on paragraph 127 0 [17] Ibid., p. 231.

¶ 128 Leave a comment on paragraph 128 0 [18] There is a simple way to verify this statement: ask anyone who is a non-specialist if she or he can name three works of hyperfiction from the last decade; then run the same question on films and novels.

¶ 129 Leave a comment on paragraph 129 0 [19] Espen J. Aarseth, Cybertext, op cit., pp. 93-94.

¶ 130 Leave a comment on paragraph 130 0 [20] Several net.art projects such as Vuk Cosic’s “Documenta Done”, 0100101110101101.org’s “Clones”, and ®TMark’s spoof web sites are simple operations of recontextualization based on the use of offline browsers.

¶ 131 Leave a comment on paragraph 131 0 [21] McKenzie Wark has described the hack as the creative gesture that turns “repetition into difference, representation into expression, communication into information.” McKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 130.

¶ 132 Leave a comment on paragraph 132 0 [22] ®TMark: Bringing IT to YOU!, Video, 1999, 11 min. Script available at http://www.rtmark.com/bityscript.html. Retrieved on August 8, 2009.

¶ 133 Leave a comment on paragraph 133 0 [23] Ibid.

¶ 134 Leave a comment on paragraph 134 0 [24] Ibid.

¶ 135 Leave a comment on paragraph 135 0 [25] Jean-Pierre Vernant, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Myth and Tragedy in Ancient Greece, trans. Janet Lloyd, New York: Zone Books, 1990, p. 43.

¶ 136 Leave a comment on paragraph 136 0 [26] See http://challenge.theyesmen.org

¶ 137 Leave a comment on paragraph 137 0 [27] See Ricardo Dominguez, Carmin Karasic, Brett Stalbaum, and Stefan Wray, “The Zapatista Tactical FloodNet: A collaborative, activist and conceptual art work of the net by Brett Stalbaum,” available at http://www.thing.net/~rdom/ecd/ZapTact.html. Retrieved on August 20, 2009.

¶ 138 Leave a comment on paragraph 138 0 [28] Sarah Ferguson, “Pecked to Death by a Duck,” Village Voice, October 17, 2000, available at www.villagevoice.com/2000-10-17/news/pecked-to-death-by-a-duck. Retrieved on September 2, 2009. The article mentions also a few figures regarding the number of participants to virtual sit-ins of the time.

¶ 139 Leave a comment on paragraph 139 0 [29] See for instance Karmin Carasic, the designer of the FloodNet interface, in Marco Deseriis and Giuseppe Marano, Net.Art. L’arte della connessione [Net.Art: The Art of Connecting], Milan: Shake, 2008, p. 151.

¶ 140 Leave a comment on paragraph 140 0 [30] Ricardo Dominguez interviewed by Coco Fusco, “Electronic Disturbance,” available at http://subsol.c3.hu/subsol_2/contributors2/domingueztext2.html. Retrieved on August 20, 2009.

¶ 141 Leave a comment on paragraph 141 0 [31] Ibid.

¶ 142 Leave a comment on paragraph 142 0 [32] Ricardo Dominguez, Bruce Simon, Geert Lovink, and Chris Carter, “Illegal Knowledge: Strategies for New Media Activism,” Electronic Book Review, July 30, 2003, available at http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/technocapitalism/mediactive. Retrieved on August 20, 2009.

¶ 143 Leave a comment on paragraph 143 0 [33] Ibid.

¶ 144 Leave a comment on paragraph 144 0 [34] Cf. Marco Deseriis and Giuseppe Marano, Net.Art, cit.

¶ 145 Leave a comment on paragraph 145 0 [35] Allucquère Rosanne Stone, The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995, p. 39. Donna J. Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York, Routledge, 1991, p. 177.

¶ 146 Leave a comment on paragraph 146 0 [36] John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” February 8, 1996. Available at http://homes.eff.org/~barlow/Declaration-Final.html. Retrieved on August 18, 2009.

¶ 147 Leave a comment on paragraph 147 0 [37] Michel Foucault, “What is an Author?” in Language, Counter Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault, (trans. and ed. by Donald F. Bouchard), Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 113-138.

¶ 148 Leave a comment on paragraph 148 0 [38] Cf. Adam Wishart and Regula Bochsler, Leaving Reality Behind: The Battle for the Soul of the Internet, London: Fourth Estate, 2002.

¶ 149 Leave a comment on paragraph 149 0 [39] Cf. “etoy.HISTORY-FILE: 15-11-99,” available at http://history.etoy.com/stories/entries/49. Retrieved on August 23, 2009.

¶ 150 Leave a comment on paragraph 150 0 [40] Joline Blais and Jon Ippolito, At the Edge of Art, London: Thames & Hudson, 2006, p. 125.

¶ 151 Leave a comment on paragraph 151 0 [41] http://toywar.etoy.com.

¶ 152 Leave a comment on paragraph 152 0 [42] agent.NASDAQ aka Reinhold Grether, “The Toywar Platform as a Monument to World Culture,” available at http://www.netzwissenschaft.de/toywar/prix00e.htm. Retrieved on August 22, 2009.

¶ 153 Leave a comment on paragraph 153 0 [43] Cf. Marco Deseriis and Giuseppe Marano, Net.Art, cit., pp. 5-17.

¶ 154 Leave a comment on paragraph 154 0 [44] Cf. Clay Shirky, Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organization, New York: Penguin, 2008.

¶ 155 Leave a comment on paragraph 155 0 [45] http://www.amazon-noir.com/press_release_nov15_2006.html. Retrieved on August 25, 2009.

¶ 156 Leave a comment on paragraph 156 0 [46] Clay Shirky, Here Comes Everybody, cit., pp. 260-92.

¶ 157 Leave a comment on paragraph 157 0 [47] Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy” in Francis Backer, Peter Hume, Margaret Iversen (eds.) Postmodernism and the Re-reading of Modernity, Manchestern University Press, 1992, p. 198.

¶ 158 Leave a comment on paragraph 158 0 [48] Tim O’Reilly, “The Architecture of Pariticipation,” O’Reilly Media, June 2004, available at http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/articles/architecture_of_participation.html. Retrieved on August 25, 2009.

The avatar’s are rather Lego-looking than Playmobil-looking.

Les Liens Invisible = missing final “s”

This should be nuanced as there was one interesting genre of “hyperfiction” that had a big success for some time in the marketplace: the “Choose Your Own Adventure” books.

Manuel,

Thanks for your feedback. You can leave your comments next to the relevant paragraph by clicking on the speech bubble next to that paragraph.

Jo